Understanding the impact of assessing EPAs

July 9, 2020

While I was still managing evaluation and assessment for an internal medicine residency program, my now-colleague Jason wrote a blog post about EPAs.

Five years later, 20 Canadian residency programs have transitioned, and the AAMC Core EPAs Pilot Project is well underway. In addition to the wealth of research and publications this has led to, we now also have an understanding of the impact of assessing EPAs.

Two challenges have been keenly felt on the ground: technology and culture change.

We’ve previously discussed the multitude of data produced when learners are being assessed more frequently, and while we’ve been working to make the technology to collect and review EPA assessments as easy as possible, the bigger challenge lands squarely on the shoulders of schools and programs.

Schools now need to change the culture of assessment, and we have seen how this impacts learners and attendings differently. While this is something that technology needs to be able to support, it cannot be the sole agent of change.

With EPAs, learners are now driving the assessment process, pushing forms to their attendings. Being the driving force to request assessments is a massive culture shift, and I’ve heard from many learners who aren’t comfortable being in the driver’s seat.

Many programs put an emphasis on the volume of assessments being a shared responsibility, but in the busy clinical setting, it can be difficult to find time in the moment for more frequent assessments. While EPA forms are often short, the increase in volume also places a bigger assessment burden on the evaluators. In some cases, we have seen this shift to senior residents, who are now both responsible for being evaluated on their own EPAs, while also assessing junior learners.

Additionally, the concept of entrustment itself has to be made clear and understandable, not only for the committee members making entrustment decisions but also for the evaluators assessing learner performance on the key tasks of the discipline.

The shift toward task-based assessment versus competencies is the first hurdle. Ole ten Cate recently clarified, “The confusion may stem from the distinction between competencies and EPAs, which I often discover is not clear to everyone. Competencies are person descriptors, as they signify what individuals are able to do, whereas EPAs are work descriptors and only reflect the work, tasks and activities that are to be carried out in health care irrespective of who does that work.”

This is not a movement away from competencies, but a new way to assess and reframe them. We’ve seen in both postgraduate and undergraduate medicine that not only are competencies embedded within EPAs, but are still assessed separately and differently.

The next hurdle is the concept of entrustment or entrustability, which, over time, has seen a shift in definition, complicating shared understanding. Additionally, attendings evaluate both undergraduate and postgraduate learners, and in many cases, EPAs for UGME vs. PGME use different entrustment-supervision (ES) scales, which can cause further confusion.

Furthermore, when ten Cate et al. compared the utility of retrospective versus prospective scales, they noted that rater preference for each scale depended on the situation. It will be interesting to follow the natural course of this research; that is, to see if the implementation of EPAs may shift to allow a unique scale for different types of EPAs.

Given that “raters are busy frontline clinical supervisors with variable training on the tool,” this is another challenge for schools to face to ensure evaluators are comfortable with these scales – and a challenge for reporting as well, as competence/entrustment committees grapple with making summative decisions on this formative feedback.

The implementation of EPAs, even the small number being piloted on the undergraduate side, is no small task, and we look forward to continuing to work with our customers to ensure that Acuity can meet these evolving challenges.

Related Articles

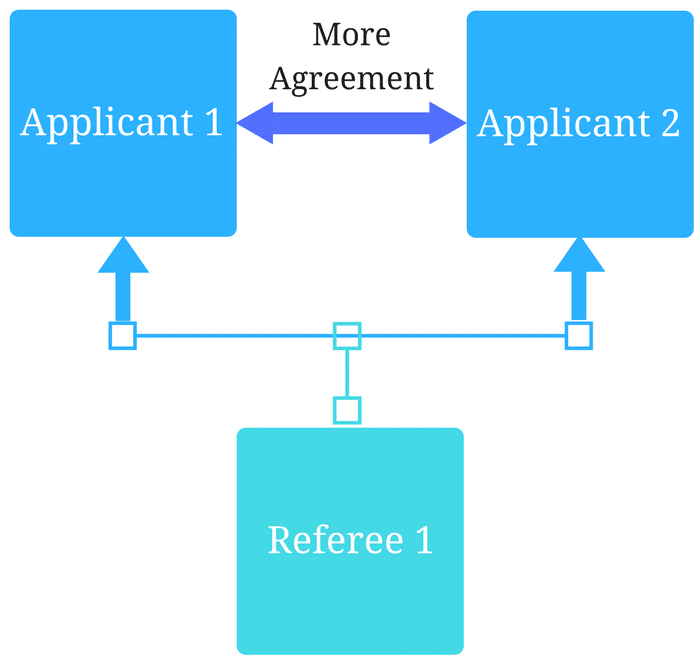

How interviews could be misleading your admissions...

Most schools consider the interview an important portion of their admissions process, hence a considerable…

Reference letters in academic admissions: useful o...

Because of the lack of innovation, there are often few opportunities to examine current legacy…