The critical role of EPAs during a global pandemic

November 24, 2020

The COVID-19 pandemic necessitated drastic changes in medical education.

As noted by Suzanne Rose in the Journal of the American Medical Association, in other disaster scenarios, medical students were able to continue their education and help. However, in a pandemic there is the increased possibility of infection, shortages of PPE, and reduction of clinical education opportunities due to canceled clinics and surgeries, among many other challenges.

Not only have we seen schools rapidly shift to online teaching at unprecedented levels – which, knowing the size and scale of medical programs is no small feat – but we have also seen schools leverage entrustable professional activities (EPAs) to make progression and graduation decisions.

This addition of task-based EPAs to a learner’s assessment portfolio provides a substantial boost in data, filling gaps – especially in more concrete clinical tasks in addition to related competencies.

Collecting EPAs

In addition to the expansion of online teaching, telehealth initiatives have also gained popularity.

We’ve seen schools add a specific EPA to capture the tasks of the discipline related to providing telemedicine or telehealth services. This EPA links with the domains of competence in Patient Care, Knowledge for Practice, Practice-based Learning & Improvement, Interpersonal & Communication Skills, as well as Personal & Professional Development.

Dicker, Singh and Sabarguna noted that by integrating multiple EPAs, a single telehealth visit would be similar to most other ambulatory clinic visits, and provide the opportunity to learn invaluable skills. This could be assessed by integrating multiple EPAs into a more competency-based assessment, rather than asking evaluators to complete multiple forms related to one encounter.

Of course, most of the EPAs in the AAMC’s Core EPA Pilot Project are observable even in telehealth consults.

We know one of the biggest challenges when transitioning to EPA-based assessments is faculty development. Adding the critical competencies or sub-tasks to a given EPA guides your faculty to provide additional constructive feedback. For example, if a learner is not able to gather essential and accurate information about the patient through history-taking, the evaluator can use that to provide feedback on how to improve that discrete skill, helping them to improve those skills over time.

Providing these cues – these sub-tasks – for evaluators can make the process of training faculty easier when transitioning to EPA-based assessments.

Using EPAs to make decisions

There is a need to graduate doctors, period, but we’ve also seen the need to graduate doctors early in the hardest hit areas. The LCME advised that medical schools could graduate their learners early, if they’d met the required competencies.

But how can a school reliably make a graduation decision with missing data?

One of the key differences between what we’ve seen between UGME and PGME is that in PGME, EPAs replaced much of the ITER-based assessments, while in UGME, EPAs are a supplement to the assessment of competencies as a whole. This means that unlike in postgrad, UGME has an even wider base from which to make decisions.

More frequent EPA assessment data about interactions in virtual and simulated environments are filling the gap, monitoring competence and performance, and ensuring Clerkships have enough data to confidently make decisions about a student’s performance and satisfactory completion of a clerkship.

The University of Calgary was already in the process of collecting EPA-based assessment data, and elected to accelerate their transition to CBME in order to create a graduation decision-making process that allowed them to make decisions that were appropriate and defensible. They changed their criteria to graduate students who were ready for reactive supervision on the 12 core EPAs of graduating medical students in Canada.

They already had most of the data needed to determine readiness for reactive supervision, noting that “a commonly referenced guideline regarding missing data is that loss of less than five percent likely has little statistical effect, whereas loss of more than 20 percent should cause us to question the validity of our findings.” As students had already completed 90 percent of their scheduled clinical clerkship experiences by the time these decisions had to be made, graduation decisions based on a nearly complete dataset could be considered valid.

Additionally, they noted that duration of clerkship training does not predict readiness for reactive supervision, which echoes what we’ve seen in the postgraduate move to CBME.

While the University of Calgary had already designed their EPAs and begun collecting the data, it’s never too late to consider adding these assessments to your assessment toolbox.

How to collect EPAs

If your program or institution has not yet made the transition to include EPA-based assessments that capture the level of supervision required for learners performing a specific EPA, there is an opportunity to begin to collect and use this data to make progression and graduation decisions.

In our discussions and research around successful roll out of CBME we understand the substantial barrier faculty development can create.

If you choose to roll out the AAMC’s Core EPAs, consider starting by implementing only two or three critical EPAs, including a telemedicine EPA if applicable, to ease your faculty and students into a different way of assessing skills.

While I always advocate for keeping assessment forms as short as possible, adding critical competencies or sub-tasks to a given EPA can help evaluators formulate better feedback for the learner. To keep things simple, these sub-tasks can be set up as checkbox questions rather than Likert questions.

Learners and faculty alike can trigger assessments anywhere they are, on their mobile devices, and complete the forms quickly and easily. As a program, you can use our Competency and EPA reports to bolster the picture you already have through knowledge exams, OSCEs, ITERs, and patient/procedure logs.

The upheaval of the pandemic has resulted in quick pivots, with a cautious eye on reducing risk especially in the MedEd environment. Beginning to assess and track performance around EPAs can fill a gap in assessment data created by increased virtual experiences, and reduce the learning curve in faculty development as CBME becomes the standard. We have seen the benefits to both learners and programs alike.

—-

Desy, J., Harvey, A., Busche, K., Weeks, S., Paget, M., Naugler, C., Welikovitch, L., & Mclaughlin, K. (2020). COVID-19, curtailed clerkships, and competency: Making graduation decisions in the midst of a global pandemic. Canadian Medical Education Journal. https://doi.org/10.36834/cmej.70432

Rose S. Medical Student Education in the Time of COVID-19. JAMA. 2020;323(21):2131–2132. doi:10.1001/jama.2020.5227

Iancu, A. M., Kemp, M. T., & Alam, H. B. (2020). Unmuting Medical Students’ Education: Utilizing Telemedicine During the COVID-19 Pandemic and Beyond. Journal of medical Internet research, 22(7), e19667. https://doi.org/10.2196/19667

Santen S.A., Ryan M.S., Coates W.C. (2020). What Can a Pandemic Teach Us About Competency-based Medical Education? AEM Education and training; 2020; 4: 316-320. https://doi.org/10.1002/aet2.10473

Related Articles

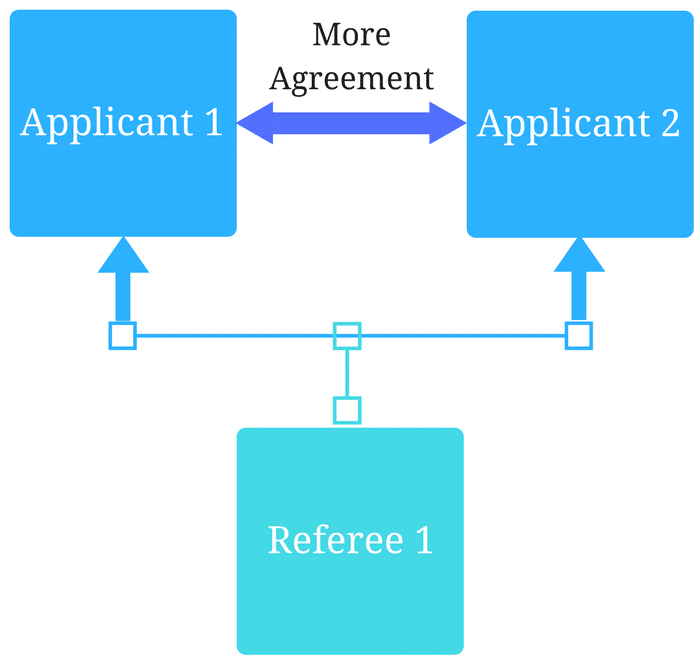

How interviews could be misleading your admissions...

Most schools consider the interview an important portion of their admissions process, hence a considerable…

Reference letters in academic admissions: useful o...

Because of the lack of innovation, there are often few opportunities to examine current legacy…