Advancing the discussion about a CBME approach to medical education

December 11, 2020

It is widely recognized that faculty development is one of the biggest challenges when implementing competency-based medical education, including adjustments both to the frequency and scope of assessment. The majority of faculty at medical schools are day-to-day clinicians, not trained educators – they are doctors who are teaching doctors.

How do you calibrate your faculty, so they are providing more consistent ratings and feedback?

It was noted that entrustment questions can feel more comfortable to faculty. After observing a learner complete a task, it is easier to understand the question, “Did you need to be there [for them to successfully complete the task]?” rather than translating what “meets expectations” could mean. While an entrustment question can be easy to answer, there still needs to be a shared mental model of what mastery of that task looks like.

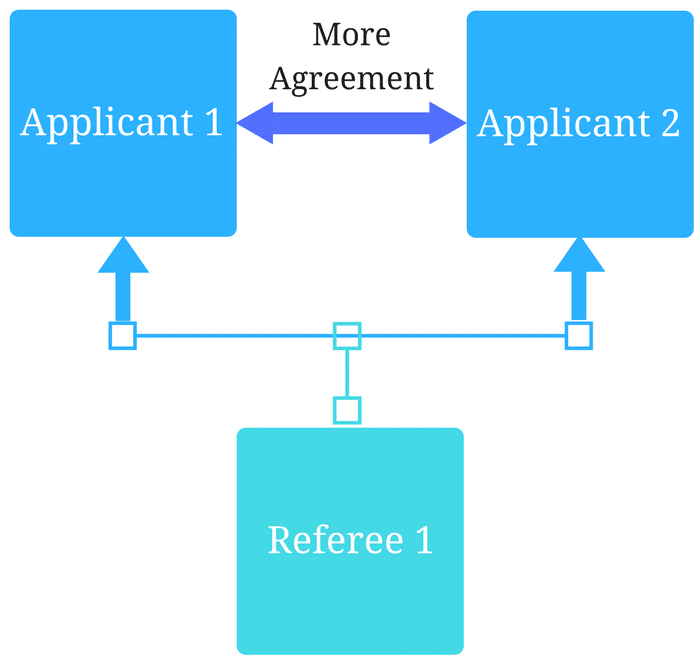

However, entrustment can also contribute to unfairness, because people can view the process of completing a given task differently. Mastery of clinical skills can vary among clinicians, and some may have adopted their own style for performing clinical tasks that may be at odds with what may be currently taught. This is where unfairness can creep into assessment methodology.

How to promote fairness?

One solution discussed was to lessen the cognitive load on raters, as assessments are most successful when they don’t ask too much of the evaluator. Intentional design of assessment forms is another way of ensuring fairness. There is a fine balance between collecting the data required to make valid and defensible entrustment and progression decisions, and not overburdening the rater. Forms that ask too much can be late, incomplete or simply not completed at all, especially when we consider the increased frequency of assessment with entrustable professional activities (EPAs).

There is evidence that forms can be less detailed if there is a large sample size, which is possible with EPAs. If you can get more data points to aggregate and synthesize, the form can be shorter and less detailed. This 2016 study demonstrates that a shortened ITER still provided valid data. We need more research in this area.

Adding critical milestones or sub-tasks to an EPA assessment guides faculty to provide additional constructive feedback, as well as defining what the critical components of the task are. This would also facilitate training faculty, since the forms themselves become guides to potential feedback to learners as well as creating a shared mental model between evaluators of what is required to complete a given task competently.

An EPA itself is a high-level task, for example, gathering a history and performing a physical examination. The AAMC core EPA pilot project schematic defines 10 expected behaviours or sub-tasks for an entrustable learner. By including those items, evaluators have more to go on than only their preferred way of completing the task to define what may be entrustable. Evaluators can use any of those expected behaviours or tasks that were missed to enhance feedback to help the learner improve for the next encounter.

My recent blog post, How EPAs are helping med schools get through Covid explores the expansion of EPAs in learner assessment over the past year and provides insights into collecting EPAs.

The potential of predictive analytics in CBME

I was also interested in the discussion about the use of predictive analytics to identify learners who may struggle with achieving entrustment on key tasks. Analysis of data sets across programs can help pinpoint those learners in advance to help them before remediation is required.

These analytics are machine powered, not human powered. But for now, human judgment is still required; we still need this contextual information. I think predictive analytics has exciting potential for making a significant improvement in medical education.

We also heard about the importance of a continuous quality improvement (CQI) mindset. Feedback loops help both the learner and the program improve. Read more in our blog post about CQI and improving accreditation outcomes.

Sometimes it seems the more we discuss CBME, the clearer it becomes that there are still a lot of unknowns. People are still looking for more definitive answers about what they should be doing.

At this point, there’s no simple step-by-step manual. We need to explore the grey areas and continue the discussion. Thanks to ICBME Collaborators for taking the lead with webinars like this.

Related Articles

How interviews could be misleading your admissions...

Most schools consider the interview an important portion of their admissions process, hence a considerable…

Reference letters in academic admissions: useful o...

Because of the lack of innovation, there are often few opportunities to examine current legacy…